The American Presidency:

Is Success Predictable?

Introduction

Predicting presidential success…a conundrum for the ages. Here we are in 2020, and about to conduct our 58th American Presidential Election. In the 57 preceding contests, there was just one that Americans were absolutely sure of electing a successful president: The first in 1788 when George Washington became the first President of the United States. Every subsequent presidential election was clouded with a certain amount of trepidation; this includes Washington’s second term in office.

Starting with the second presidential election in 1792, politicians, academia, pundits, political strategists, historians and the American public, have tried to figure out what it takes to predict a successful presidency. The first problem, however, is simply the fact that what it takes to get nominated, then get elected, and finally succeeding in the Presidency, are three different things entirely. In a very real sense, each of these three processes are largely done on a standalone basis, with different factors & people, wanted & unwanted, that shape the man and the results throughout his journey.

Some Presidents have really applied themselves at times along the way; at other times they were the unexpected beneficiary of good fortune; some were the architect of their own disaster, and sometimes they were the unwitting recipient of poor timing or bad luck. For some Presidents, the office became like hell-on-earth, though they themselves were not ill-intentioned. Some Presidents acknowledged the poor choices they made, like Ulysses Grant did in his final address to Congress regarding his choice of several cabinet secretaries who turned out to be dishonest. Other Presidents worked hard, but, died in office, and only after their death did the public learn of scandal, turning the man’s presidency into a hell-of-a-mess. As the saying goes: “sometimes the road to hell is paved with good intentions.”

As you will see in the following discussion, predicting Presidential Success is not a tried n’ true process, or there would have been a lot more successful men in the Oval Office. The processes of finding, developing and electing Presidents have changed quite a bit. But, none of those things have improved the odds of Presidential success after the inauguration is over!

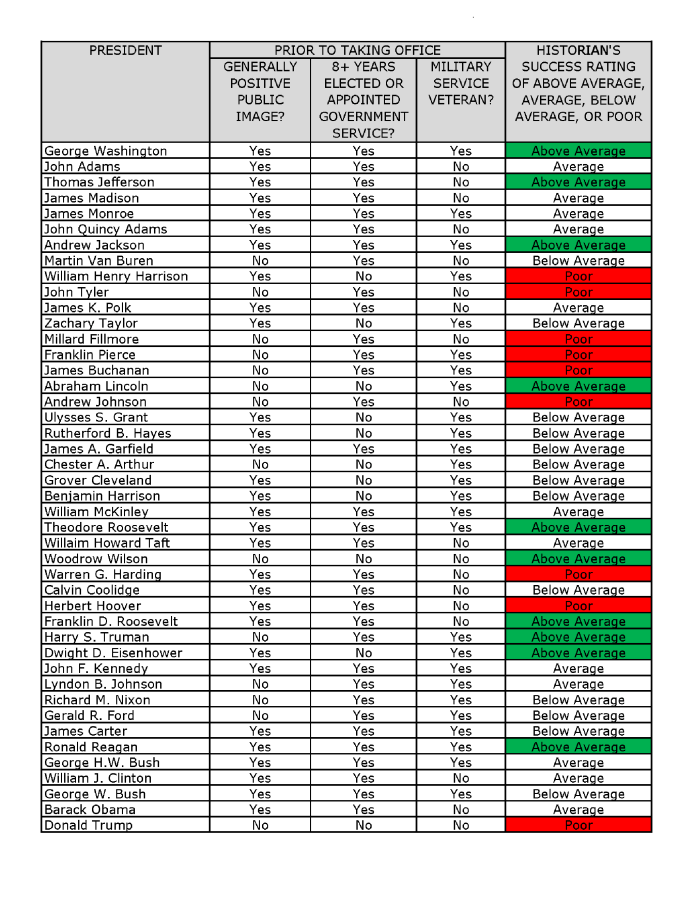

Factors and Traits of Presidents Prior to Taking Office

For this part of the discussion, see the Chart of the Presidents below. Since the first Presidential Election in 1788, George Washington set the bar for positive factors and traits the public could look for in choosing, hopefully, a successful President. But, are these things really valid in determining Presidential success? If you think about it, a positive public image, significant public service time, and being a military veteran, are things that George Washington’s admirers seized upon in trumpeting their support of his Presidential candidacy. In the Presidential Elections of 1788 and 1792, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were Washington’s competitors. Although neither man served in the military, their contributions in forming the United States of America were highly regarded, and easily eclipsed everyone else except Washington. In either man’s case, however, they did not risk life & limb on the battlefield, nor suffer the privations of war like George Washington. The fact did not escape anyone’s attention that the American Revolution had to be won on the battlefield against the greatest army in the world, not by diplomacy or politics. Washington clearly had all of the boxes checked for winning two Presidential Elections.

Washington’s successful Presidency was aided by the three characteristics mentioned above, but, they were not the real story. Additional one-time factors in Washington’s success were: he was the first President, setting the precedent for defining success, and; he was America’s symbol of a new nation that was not led by a monarchy. Subsequent Presidents would not have the luxury of these one-time positive characteristics.

Although the public seized upon Washington’s popularity, prior public service and war hero status, they were all extrinsic factors that were no guarantee of success. Rather, Washington’s intrinsic abilities, such as leadership, a shrewd judge of character and clear thinking under pressure, benefited him far more than what was on public display.

The Top-Rated Presidents

In the historical rating of Presidential success, Washington and nine other men have rated above average, including: Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Ronald Reagan. Of these nine Presidents, only Andrew Jackson, Theodore Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan, had all three of Washington’s pre-election characteristics of public image, public service and military service. Were any of these factors clearly more important to voters at election time? In the case of Jackson and Roosevelt, they were both war heroes, and Reagan cashed-in on his movie star fame. But, none of the three pre-election positive characteristics made them successful Presidents. Let’s take a look at the nine Presidents who rated above average like George Washington.

- Thomas Jefferson. No one expected Jefferson to be any less of a success than Washington, and he did not disappoint. Did his popularity and public office experience help his success? Those extrinsic factors may have helped indirectly, but, Jefferson’s intrinsic traits of intelligence, leadership and innate critical thinking skills carried the day. His greatest achievements included the massive Louisiana Purchase of land, projected American power overseas with the U.S. Navy, and recalibrated the economy by shrinking the Federal Government & National Debt.

- Andrew Jackson. Jackson’s war hero status made him popular with the working-class. He was the first President not from Virginia or Massachusetts; he hailed from rural Nashville, TN. Jackson was a controversial President, with plenty of detractors. He did, however, provide another critical recalibration of American society & government, similar to Jefferson. His strong moral compass guided his success by pushing to payoff the National Debt, and slow the enrichment of east coast bankers and their wealthy clientele. Jackson’s sense of right & wrong would be sorely tested throughout his eight years in office.

- Ronald Reagan. Reagan’s communication skills are probably better than any other President in American history. These skills, however, go far beyond just writing and speaking. He understood how to develop a plot, a story, how to act your way through a scene, such that, he had no disbelievers, especially the Soviets. Reagan sensed the timing was right to push Soviet Communism over the cliff of economic disaster. He did this by a massive increase in defense spending that accomplished two goals: It pulled the American economy out of a deep recession, and it forced the Soviets to spend huge amounts of money they did not have on a military build up.

The other above average Presidents had varying degrees of George Washington’s pre-election characteristics, including one President with only one of the traits, and another man who had none of them! It really demonstrates that whatever characteristics a President had or did not have prior to election, did not necessarily guarantee success. For example, except for Abraham Lincoln’s two years of military service in the 1840s, he was not elected based on popularity, and he had limited public office experience. Lincoln was clearly a once-in-a-millenium leader who unexpectedly rose to the occasion, surprising millions. Woodrow Wilson never served in the military, had just two years of experience as Governor of New Jersey, and was clearly not the most popular presidential candidate. Had Theodore Roosevelt not split the Republican vote by trying to reenter politics against the popular President William Howard Taft, Wilson would not have won the election. In spite of having none of the pre-election appeal of Taft or Roosevelt, and a belief that his intelligence was superior to everyone, Wilson did well in handling the enactment of child labor laws, creation of the Federal Reserve System, Women’s Suffrage, and keeping America out of the First World War for the first three out of four years.

Three of the remaining four Presidents, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman were successful, and often at odds with their own political party. Both Roosevelts graduated from Harvard and the Columbia Law School, but, Truman dropped out of college after one year. Theodore Roosevelt’s greatest successes include going up against his own contemporaries, like J.P. Morgan, to enact legislation and push through the courts the break-up of some of the world’s largest business trusts and monopolies. Roosevelt also revamped the Interior Department by creating the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service. Roosevelt was the first president to push for conservation of natural resources during an era when little regard was paid to deforestation and animal extinction. Franklin Roosevelt also eschewed his wealthy upbringing by lifting-up the country through numerous measures to vanquish the Great Depression. He also successfully led the free world to victory in World War II. And Harry Truman, a no nonsense, mid-westerner from Missouri, first became a local politician through a big-time Democratic Party boss in Kansas City. It eventually led Truman to the U.S. Senate, where he proved he was his own man, not a puppet Democratic Party hack. While President, he took ownership for some of the toughest decisions ever made in the Oval Office, such as: dropping the atomic bomb on Japan, and firing 5-star general, Douglas MacArthur, for insubordination during the Korean War.

Dwight Eisenhower is the final President with a successful rating. Just like Donald Trump, Eisenhower had never held a political office. His strong organizational skills as 5-star Army general carried him throughout his eight years. Eisenhower made solid cabinet selections who were fiercely loyal to him. His cabinet turnover in eight years is less than what Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush had in just four-year terms.

The Least Successful Presidents

The Presidents who consistently rate poorly are mostly justified. They all had reasonably good credentials prior to taking office, but, none of it helped them in avoiding an unsuccessful Presidency. Some like William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor, were extremely popular Army generals and war heroes, but, had the misfortune of dying after a short time in office.

President John Tyler, has been rated poorly when he really should not be. Tyler was Vice President and took over the Presidency from Harrison after dying of pneumonia only 30 days into his term. Tyler was the first Vice President to exercise the Constitution’s provision of Presidential Succession. The Constitution did not specify what should happen after Tyler took office, and this created a crisis in Congress. Tyler took the step, and thereby set the precedent, that the Constitution said he was supposed to be the President, and with no further clarification, that was that. Congressional leaders were outraged, and excoriated Tyler at every opportunity. In retrospect, Tyler did all of us a favor by setting the example of how a Vice President should conduct himself after replacing the person the public really wanted in the Oval Office.

The Tyler scenario would happen again when Millard Fillmore took over for the deceased Zachary Taylor. Fillmore also collared a poor rating. Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan received poor ratings for doing nothing to prevent the Civil War. And Lincoln’s replacement, Andrew Johnson, is always rated poorly for his mishandling of Reconstruction following the Civil War.

Warren G. Harding was elected in 1920 and was wildly popular, but, died two and a half years after taking office. Up to that point he had performed well. After Harding died, however, and thus unable to deal with any future problems, it came to light that several of his Cabinet members had defrauded the Government while in office. It also came out that Harding had fathered two illegitimate children, and the mothers were being paid ongoing hush money by political operatives to remain quiet. There is no evidence that Harding knew about his dishonest cabinet secretaries, or that the two women he had affairs with were being paid-off. In either case, Harding’s Presidency was tainted and rated poorly ever since.

The last President with a poor rating is Donald Trump. Trump shares the dubious distinction with Woodrow Wilson of having none of George Washington’s pre-election favorable characteristics. Wilson made those characteristics a non-factor in his Presidency, even when his lack of likability persisted throughout his time in office, and has never really changed. It is difficult to say whether Trump’s Presidential legacy will be judged unsuccessful or not…time will tell.

Does the Perspective of Time Change Things?

Of all the men who have been President of the United States, only five have seen any change in their success rating. Three have improved, and two have worsened. Just like having some, or all three of Washington’s pre-election favorable characteristics were not very helpful in predicting Presidential success, neither has the passage of time, nor a better informed populace, changed a President’s success rating from when they first left office.

The three Presidents who have seen some minor improvement from poor to below average are: Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S. Grant, and George W. Bush. Taylor’s slight improvement is due to historians looking at his 18 months of service and concluding he actually accomplished some good, and should not be collared with a poor rating just because he had the misfortune of dying in office. In Grant’s case, he had a poor rating for more than 120 years. He has inched-up in the past 30 years after historians decided that his numerous dishonest cabinet appointees that pulled him down, should not completely outweigh Grant’s success in resolving the headaches of Reconstruction.

When George Bush left office, he had a low approval rating and graded-out poorly in terms of success, largely due to the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. President Obama took office on a campaign promise to finish the job in both countries and bring the troops home. Neither war zone was mopped-up as planned, even after Obama sent in more troops. When Obama’s team ran into problems with the Iraqi government in negotiating a new SOFA (status of forces agreement), the President ordered American forces to pack-up and leave. As a result of America’s departure, ISIS filled the void, and it took three years and the virtual destruction of Iraq’s second largest city, Mosul, to eradicate the insurgency. In terms of President Obama’s success rating, it would be difficult to rate his Presidency as level two average, but, leave Bush at level four poor, for the Iraqi and Afghan quagmires, when his successor did no better. So, it only seems fair that Bush has moved upward from poor to below average.

The two Presidents who’s ratings dropped were two term President Grover Cleveland, and Herbert Hoover. Cleveland served during the 1880-1890 timeframe. For more than 100 years, Cleveland’s success rating had been level two average. Over the past 20 years, however, Cleveland’s rating has slipped to below average. Similarly, Herbert Hoover, who served from 1929 to 1933, had his success rating drop from below average to poor. Why would these two Presidents see their ratings drop? In simple terms, they presided over an economic collapse. I will further explain below.

Well respected historians have an unwritten professional code: You research history, analyze history, and write about history, but, you do not make history. Historians enjoy finding new pieces of information about a previously well covered topic. They are careful, however, in putting the new information in the proper context of preexisting information. It is one thing to enhance or flesh-out an existing story, but, historians are loathe to be revisionists for the sake of stirring-up controversy, or self-aggrandizement. This is why 39 out of 44 American Presidents have largely retained their success rating from the time they left office, until present day.

Understanding historical context is critical to evaluating events from a bygone era. Presidential success ratings were assigned within the context of what historians and the public living in that era witnessed themselves. We have the benefit of hindsight; they did not. Here are a few examples to illustrate the point. It was known then, and it is well documented now, that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson owned slaves. In modern times someone might conclude that Washington and Jefferson were racists. But, within the context of the times and locale they lived in, was that a universally accepted definition? No, it was not. It stands to reason that neither President’s success rating should be lowered based on a modern day definition.

We can also look at the opposite circumstance where a modern day definition of a successful Presidency could elevate a rating. Take James K. Polk, for example, who served one term in the 1840s. Polk had previously served as the Speaker of the House of Representatives, but, in the 1844 election, he was completely out of politics. Polk was nominated at the Democratic Convention as a compromise candidate after several dozen rounds of voting failed to select a candidate. Polk’s nomination & candidacy is what spawned the now famous phrase of being a “dark horse candidate. When Polk accepted the nomination, he promised to only serve one term, and he did just that. Polk, however, accomplished something that no other President before or since has ever done: He successfully completed all four of his four major campaign promises. By modern day standards, that is considered nothing short of a miracle. But, by 1840’s standards, Polk was merely seen as having done the job he was elected to do. Polk’s level two average rating has never been elevated to the top level.

The foregoing examples demonstrate the reluctance of modern day historians and political scientists to alter a past President’s original success rating, with only a few exceptions. Circling back to Grover Cleveland and Herbert Hoover, what caused a shift in their ratings? In Cleveland’s case he is the only President to serve two non-consecutive terms. He served from 1885-1889, and 1893-1897, with President Benjamin Harrison sandwiched in between. By time the 1892 election came around, the economic and financial changes occurring during Harrison’s tenure were perceived as needing a President “who knew what he was doing.” This led to Cleveland’s reelection. However, politicians at the time, and well into the 1930s, knew little about economics, big business and the financial markets. There was still a strong belief that financial problems were cyclical and had a way of working themselves out. When the Panic of 1893 hit, Cleveland failed to take the right actions to fix things, and the economic plunge persisted for his entire second term. Likewise, Herbert Hoover was at the helm when the stock market crashed in 1929, leading to the Great Depression. Hoover was not aggressive enough in taking government action, thinking like Cleveland that the economy and financial markets would self-correct; they did not.

Cleveland and Hoover did not take all of the blame for the two economic disasters. Cleveland, for more than 100 years, was rated level two average, and Hoover was rated level three below average. Two subsequent financial meltdowns seem to have changed historical sentiment for both men. Jimmy Carter supervised a huge recession with double digit inflation, and double digit unemployment, from 1977-1981, and made no headway is resolving the crisis. In 2008, President Bush was in the Oval Office when the mortgage banking industry collapsed. After witnessing the events of 1977-1981, and the 2008 collapse, historians, politicians and the public decided that President’s actually had the power and responsibility to either reduce the likelihood of a financial collapse, or step-in to lead a recovery. So, while revisionists were addressing Carter’s failure, and ensuring Bush took the appropriate blame, eyes were cast back to Cleveland and Hoover’s economic supervision during their tenure. Revisionists have decided that both Presidents were really “asleep at the switch,” and could have done far more to cushion the collapse. Cleveland’s Presidential success has been lowered to level three below average, and Hoover’s has dropped to level four poor.

Summary

A President’s pre-election traits and skills are rarely a good barometer of Presidential Success. Success is normally attributable to a President’s intrinsic capabilities, and how he applies, or fails to apply them. Success ratings pinned on a President as he leaves office, normally remain unchanged regardless the passage of time, even when things are better understood later on. If a success rating is changed, the evidence to do so must be clear, and universally convincing. One thing that does change after a President leaves office is: For better or worse, a departing President is no longer the same man he was when he first entered the White House; things will never be the same for him. As the 1940s author, Thomas Wolfe said: “you can never go home again.”

Ciao,

Steve Miller

Editor

The Report on National Security Kinetics™

Seattle, WA. USA

vietvetsteve@millermgmtsys.com