I wrote this quote several years ago. It seems to be appropriate for the Biden Administration’s constant carping about Israel’s operational methods in eradicating Hamas.

I wrote this quote several years ago. It seems to be appropriate for the Biden Administration’s constant carping about Israel’s operational methods in eradicating Hamas.

Predicting presidential success…a conundrum for the ages. Here we are in 2020, and about to conduct our 58th American Presidential Election. In the 57 preceding contests, there was just one that Americans were absolutely sure of electing a successful president: The first in 1788 when George Washington became the first President of the United States. Every subsequent presidential election was clouded with a certain amount of trepidation; this includes Washington’s second term in office.

Starting with the second presidential election in 1792, politicians, academia, pundits, political strategists, historians and the American public, have tried to figure out what it takes to predict a successful presidency. The first problem, however, is simply the fact that what it takes to get nominated, then get elected, and finally succeeding in the Presidency, are three different things entirely. In a very real sense, each of these three processes are largely done on a standalone basis, with different factors & people, wanted & unwanted, that shape the man and the results throughout his journey.

Some Presidents have really applied themselves at times along the way; at other times they were the unexpected beneficiary of good fortune; some were the architect of their own disaster, and sometimes they were the unwitting recipient of poor timing or bad luck. For some Presidents, the office became like hell-on-earth, though they themselves were not ill-intentioned. Some Presidents acknowledged the poor choices they made, like Ulysses Grant did in his final address to Congress regarding his choice of several cabinet secretaries who turned out to be dishonest. Other Presidents worked hard, but, died in office, and only after their death did the public learn of scandal, turning the man’s presidency into a hell-of-a-mess. As the saying goes: “sometimes the road to hell is paved with good intentions.”

As you will see in the following discussion, predicting Presidential Success is not a tried n’ true process, or there would have been a lot more successful men in the Oval Office. The processes of finding, developing and electing Presidents have changed quite a bit. But, none of those things have improved the odds of Presidential success after the inauguration is over!

For this part of the discussion, see the Chart of the Presidents below. Since the first Presidential Election in 1788, George Washington set the bar for positive factors and traits the public could look for in choosing, hopefully, a successful President. But, are these things really valid in determining Presidential success? If you think about it, a positive public image, significant public service time, and being a military veteran, are things that George Washington’s admirers seized upon in trumpeting their support of his Presidential candidacy. In the Presidential Elections of 1788 and 1792, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were Washington’s competitors. Although neither man served in the military, their contributions in forming the United States of America were highly regarded, and easily eclipsed everyone else except Washington. In either man’s case, however, they did not risk life & limb on the battlefield, nor suffer the privations of war like George Washington. The fact did not escape anyone’s attention that the American Revolution had to be won on the battlefield against the greatest army in the world, not by diplomacy or politics. Washington clearly had all of the boxes checked for winning two Presidential Elections.

Washington’s successful Presidency was aided by the three characteristics mentioned above, but, they were not the real story. Additional one-time factors in Washington’s success were: he was the first President, setting the precedent for defining success, and; he was America’s symbol of a new nation that was not led by a monarchy. Subsequent Presidents would not have the luxury of these one-time positive characteristics.

Although the public seized upon Washington’s popularity, prior public service and war hero status, they were all extrinsic factors that were no guarantee of success. Rather, Washington’s intrinsic abilities, such as leadership, a shrewd judge of character and clear thinking under pressure, benefited him far more than what was on public display.

In the historical rating of Presidential success, Washington and nine other men have rated above average, including: Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Ronald Reagan. Of these nine Presidents, only Andrew Jackson, Theodore Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan, had all three of Washington’s pre-election characteristics of public image, public service and military service. Were any of these factors clearly more important to voters at election time? In the case of Jackson and Roosevelt, they were both war heroes, and Reagan cashed-in on his movie star fame. But, none of the three pre-election positive characteristics made them successful Presidents. Let’s take a look at the nine Presidents who rated above average like George Washington.

The other above average Presidents had varying degrees of George Washington’s pre-election characteristics, including one President with only one of the traits, and another man who had none of them! It really demonstrates that whatever characteristics a President had or did not have prior to election, did not necessarily guarantee success. For example, except for Abraham Lincoln’s two years of military service in the 1840s, he was not elected based on popularity, and he had limited public office experience. Lincoln was clearly a once-in-a-millenium leader who unexpectedly rose to the occasion, surprising millions. Woodrow Wilson never served in the military, had just two years of experience as Governor of New Jersey, and was clearly not the most popular presidential candidate. Had Theodore Roosevelt not split the Republican vote by trying to reenter politics against the popular President William Howard Taft, Wilson would not have won the election. In spite of having none of the pre-election appeal of Taft or Roosevelt, and a belief that his intelligence was superior to everyone, Wilson did well in handling the enactment of child labor laws, creation of the Federal Reserve System, Women’s Suffrage, and keeping America out of the First World War for the first three out of four years.

Three of the remaining four Presidents, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman were successful, and often at odds with their own political party. Both Roosevelts graduated from Harvard and the Columbia Law School, but, Truman dropped out of college after one year. Theodore Roosevelt’s greatest successes include going up against his own contemporaries, like J.P. Morgan, to enact legislation and push through the courts the break-up of some of the world’s largest business trusts and monopolies. Roosevelt also revamped the Interior Department by creating the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service. Roosevelt was the first president to push for conservation of natural resources during an era when little regard was paid to deforestation and animal extinction. Franklin Roosevelt also eschewed his wealthy upbringing by lifting-up the country through numerous measures to vanquish the Great Depression. He also successfully led the free world to victory in World War II. And Harry Truman, a no nonsense, mid-westerner from Missouri, first became a local politician through a big-time Democratic Party boss in Kansas City. It eventually led Truman to the U.S. Senate, where he proved he was his own man, not a puppet Democratic Party hack. While President, he took ownership for some of the toughest decisions ever made in the Oval Office, such as: dropping the atomic bomb on Japan, and firing 5-star general, Douglas MacArthur, for insubordination during the Korean War.

Dwight Eisenhower is the final President with a successful rating. Just like Donald Trump, Eisenhower had never held a political office. His strong organizational skills as 5-star Army general carried him throughout his eight years. Eisenhower made solid cabinet selections who were fiercely loyal to him. His cabinet turnover in eight years is less than what Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush had in just four-year terms.

The Presidents who consistently rate poorly are mostly justified. They all had reasonably good credentials prior to taking office, but, none of it helped them in avoiding an unsuccessful Presidency. Some like William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor, were extremely popular Army generals and war heroes, but, had the misfortune of dying after a short time in office.

President John Tyler, has been rated poorly when he really should not be. Tyler was Vice President and took over the Presidency from Harrison after dying of pneumonia only 30 days into his term. Tyler was the first Vice President to exercise the Constitution’s provision of Presidential Succession. The Constitution did not specify what should happen after Tyler took office, and this created a crisis in Congress. Tyler took the step, and thereby set the precedent, that the Constitution said he was supposed to be the President, and with no further clarification, that was that. Congressional leaders were outraged, and excoriated Tyler at every opportunity. In retrospect, Tyler did all of us a favor by setting the example of how a Vice President should conduct himself after replacing the person the public really wanted in the Oval Office.

The Tyler scenario would happen again when Millard Fillmore took over for the deceased Zachary Taylor. Fillmore also collared a poor rating. Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan received poor ratings for doing nothing to prevent the Civil War. And Lincoln’s replacement, Andrew Johnson, is always rated poorly for his mishandling of Reconstruction following the Civil War.

Warren G. Harding was elected in 1920 and was wildly popular, but, died two and a half years after taking office. Up to that point he had performed well. After Harding died, however, and thus unable to deal with any future problems, it came to light that several of his Cabinet members had defrauded the Government while in office. It also came out that Harding had fathered two illegitimate children, and the mothers were being paid ongoing hush money by political operatives to remain quiet. There is no evidence that Harding knew about his dishonest cabinet secretaries, or that the two women he had affairs with were being paid-off. In either case, Harding’s Presidency was tainted and rated poorly ever since.

The last President with a poor rating is Donald Trump. Trump shares the dubious distinction with Woodrow Wilson of having none of George Washington’s pre-election favorable characteristics. Wilson made those characteristics a non-factor in his Presidency, even when his lack of likability persisted throughout his time in office, and has never really changed. It is difficult to say whether Trump’s Presidential legacy will be judged unsuccessful or not…time will tell.

Of all the men who have been President of the United States, only five have seen any change in their success rating. Three have improved, and two have worsened. Just like having some, or all three of Washington’s pre-election favorable characteristics were not very helpful in predicting Presidential success, neither has the passage of time, nor a better informed populace, changed a President’s success rating from when they first left office.

The three Presidents who have seen some minor improvement from poor to below average are: Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S. Grant, and George W. Bush. Taylor’s slight improvement is due to historians looking at his 18 months of service and concluding he actually accomplished some good, and should not be collared with a poor rating just because he had the misfortune of dying in office. In Grant’s case, he had a poor rating for more than 120 years. He has inched-up in the past 30 years after historians decided that his numerous dishonest cabinet appointees that pulled him down, should not completely outweigh Grant’s success in resolving the headaches of Reconstruction.

When George Bush left office, he had a low approval rating and graded-out poorly in terms of success, largely due to the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. President Obama took office on a campaign promise to finish the job in both countries and bring the troops home. Neither war zone was mopped-up as planned, even after Obama sent in more troops. When Obama’s team ran into problems with the Iraqi government in negotiating a new SOFA (status of forces agreement), the President ordered American forces to pack-up and leave. As a result of America’s departure, ISIS filled the void, and it took three years and the virtual destruction of Iraq’s second largest city, Mosul, to eradicate the insurgency. In terms of President Obama’s success rating, it would be difficult to rate his Presidency as level two average, but, leave Bush at level four poor, for the Iraqi and Afghan quagmires, when his successor did no better. So, it only seems fair that Bush has moved upward from poor to below average.

The two Presidents who’s ratings dropped were two term President Grover Cleveland, and Herbert Hoover. Cleveland served during the 1880-1890 timeframe. For more than 100 years, Cleveland’s success rating had been level two average. Over the past 20 years, however, Cleveland’s rating has slipped to below average. Similarly, Herbert Hoover, who served from 1929 to 1933, had his success rating drop from below average to poor. Why would these two Presidents see their ratings drop? In simple terms, they presided over an economic collapse. I will further explain below.

Well respected historians have an unwritten professional code: You research history, analyze history, and write about history, but, you do not make history. Historians enjoy finding new pieces of information about a previously well covered topic. They are careful, however, in putting the new information in the proper context of preexisting information. It is one thing to enhance or flesh-out an existing story, but, historians are loathe to be revisionists for the sake of stirring-up controversy, or self-aggrandizement. This is why 39 out of 44 American Presidents have largely retained their success rating from the time they left office, until present day.

Understanding historical context is critical to evaluating events from a bygone era. Presidential success ratings were assigned within the context of what historians and the public living in that era witnessed themselves. We have the benefit of hindsight; they did not. Here are a few examples to illustrate the point. It was known then, and it is well documented now, that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson owned slaves. In modern times someone might conclude that Washington and Jefferson were racists. But, within the context of the times and locale they lived in, was that a universally accepted definition? No, it was not. It stands to reason that neither President’s success rating should be lowered based on a modern day definition.

We can also look at the opposite circumstance where a modern day definition of a successful Presidency could elevate a rating. Take James K. Polk, for example, who served one term in the 1840s. Polk had previously served as the Speaker of the House of Representatives, but, in the 1844 election, he was completely out of politics. Polk was nominated at the Democratic Convention as a compromise candidate after several dozen rounds of voting failed to select a candidate. Polk’s nomination & candidacy is what spawned the now famous phrase of being a “dark horse candidate. When Polk accepted the nomination, he promised to only serve one term, and he did just that. Polk, however, accomplished something that no other President before or since has ever done: He successfully completed all four of his four major campaign promises. By modern day standards, that is considered nothing short of a miracle. But, by 1840’s standards, Polk was merely seen as having done the job he was elected to do. Polk’s level two average rating has never been elevated to the top level.

The foregoing examples demonstrate the reluctance of modern day historians and political scientists to alter a past President’s original success rating, with only a few exceptions. Circling back to Grover Cleveland and Herbert Hoover, what caused a shift in their ratings? In Cleveland’s case he is the only President to serve two non-consecutive terms. He served from 1885-1889, and 1893-1897, with President Benjamin Harrison sandwiched in between. By time the 1892 election came around, the economic and financial changes occurring during Harrison’s tenure were perceived as needing a President “who knew what he was doing.” This led to Cleveland’s reelection. However, politicians at the time, and well into the 1930s, knew little about economics, big business and the financial markets. There was still a strong belief that financial problems were cyclical and had a way of working themselves out. When the Panic of 1893 hit, Cleveland failed to take the right actions to fix things, and the economic plunge persisted for his entire second term. Likewise, Herbert Hoover was at the helm when the stock market crashed in 1929, leading to the Great Depression. Hoover was not aggressive enough in taking government action, thinking like Cleveland that the economy and financial markets would self-correct; they did not.

Cleveland and Hoover did not take all of the blame for the two economic disasters. Cleveland, for more than 100 years, was rated level two average, and Hoover was rated level three below average. Two subsequent financial meltdowns seem to have changed historical sentiment for both men. Jimmy Carter supervised a huge recession with double digit inflation, and double digit unemployment, from 1977-1981, and made no headway is resolving the crisis. In 2008, President Bush was in the Oval Office when the mortgage banking industry collapsed. After witnessing the events of 1977-1981, and the 2008 collapse, historians, politicians and the public decided that President’s actually had the power and responsibility to either reduce the likelihood of a financial collapse, or step-in to lead a recovery. So, while revisionists were addressing Carter’s failure, and ensuring Bush took the appropriate blame, eyes were cast back to Cleveland and Hoover’s economic supervision during their tenure. Revisionists have decided that both Presidents were really “asleep at the switch,” and could have done far more to cushion the collapse. Cleveland’s Presidential success has been lowered to level three below average, and Hoover’s has dropped to level four poor.

A President’s pre-election traits and skills are rarely a good barometer of Presidential Success. Success is normally attributable to a President’s intrinsic capabilities, and how he applies, or fails to apply them. Success ratings pinned on a President as he leaves office, normally remain unchanged regardless the passage of time, even when things are better understood later on. If a success rating is changed, the evidence to do so must be clear, and universally convincing. One thing that does change after a President leaves office is: For better or worse, a departing President is no longer the same man he was when he first entered the White House; things will never be the same for him. As the 1940s author, Thomas Wolfe said: “you can never go home again.”

Ciao,

Steve Miller

Editor

The Report on National Security Kinetics™

Seattle, WA. USA

vietvetsteve@millermgmtsys.com

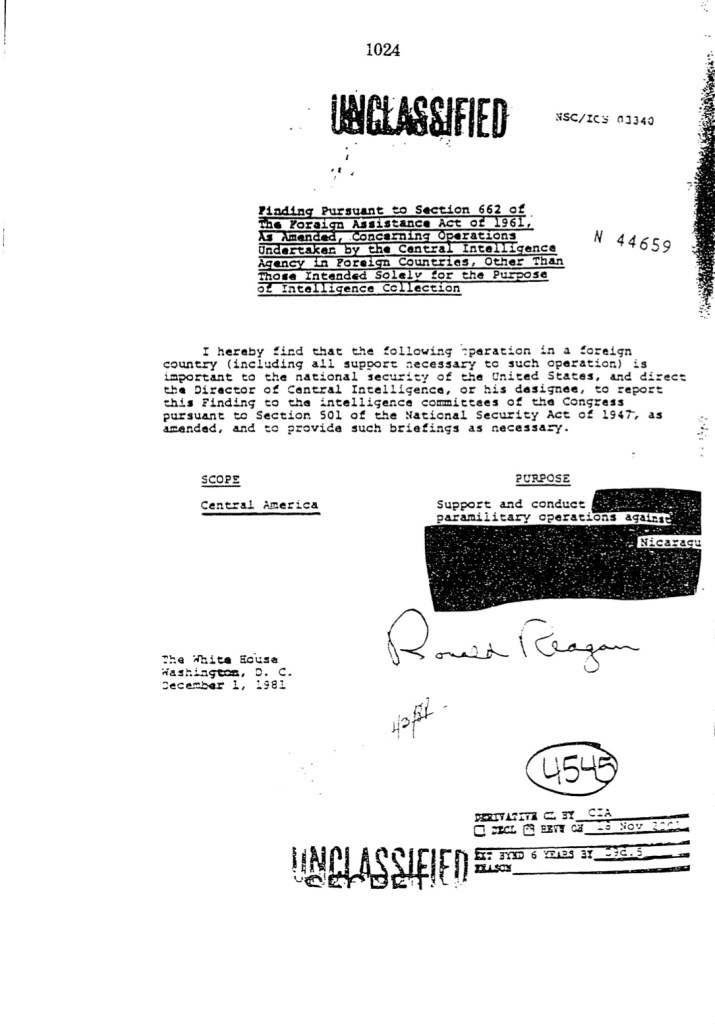

Presidential Finding signed by President Reagan to authorize the CIA to conduct covert operations in Central America to aid the Contra rebels in their fight against the Communist-backed Sandinista government in Nicaraqua.

Presidential Finding signed by President Reagan to authorize the CIA to conduct covert operations in Central America to aid the Contra rebels in their fight against the Communist-backed Sandinista government in Nicaraqua.

During the Vietnam War nearly every kind of intelligence operation you can think of was undertaken by the U.S. Intelligence Community. The four most heavily engaged agencies, starting with the most utilized first, were: the Central Intelligence Agency, Defense Intelligence Agency, National Security Agency, and the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research. As the War dragged on, with public, Congressional, and Presidential frustration mounting, increased pressure was applied on intelligence activities, especially the CIA, to help turn the War in a more positive direction.

Thomas Ahern, a CIA intelligence officer, who started his career in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War, wrote an excellent book, “Vietnam Declassified,” about the CIA and the many types of intelligence operations undertaken in Vietnam. He cites an exasperating meeting about a problem with a certain pacification program led by the CIA, during which someone tossed out a new idea. William Colby (future CIA director), who was the CIA’s Saigon station chief at the time, replied that he was willing to try anything—if it would work. The mounting, across-the-board frustration, left the CIA and its cohort agencies, grasping at straws.

William Colby became the new Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) in September 1973, just a month after American combat activity ceased in Southeast Asia. Colby’s tenure would be a brief 2 ½ years. Before the year was over, allegations began to surface in the press about questionable intelligence activities during the War. Press allegations continued throughout 1974, and murmurings started-up in Congress about possible Intelligence Community improprieties. By time Colby left office he would arguably hold the distinction of testifying before Congress more than any other DCI. By January 1975 both the Senate, and House of Representatives, were conducting hearings about the impropriety allegations. Senator Frank Church chaired one committee, and Congressman Otis Pike chaired a similar investigation committee in the House.

All of this external attention on the Intelligence Community resulted in passage of several new laws to tighten-up accountability and oversight of certain critical, intelligence operations. For the most part, the type of operations that were closely looked at, and caused the most angst with Congress, were those in which the importance to U.S. National Security was ill-defined; in essence, justifying a direct benefit to the Unites States was a stretch, at best.

U.S. Foreign Policy has a range of options available to the President in order to achieve his goals. The low end of the scale espouses the use of diplomacy to achieve American goals overseas. At the opposite end of the spectrum from diplomacy is military intervention. Starting in the post-World War II era, and continuing to this day, foreign relations between countries have become so complex that often times using pure diplomacy is ineffective; but, military intervention is too much. The gray area between State Department diplomacy, and Defense Department military operations, is often the domain of the CIA using Covert Action to achieve American foreign policy goals. It is this genre of intelligence operations that garnered such a strong backlash from Congress and the public after Vietnam.

Regardless the type of intelligence operation being mounted, they all have an appropriate level of Operational Security – “OPSEC.” OPSEC is usually manifested in three categories:

• Clandestine operation: An operation sponsored or conducted by a U.S. government department or agency in such a way as to assure secrecy or concealment. Clandestine operations are the usual means of OPSEC for espionage and/or intelligence collection, which is the “bread n’ butter” spying conducted by the CIA’s National Clandestine Service. The biggest reason intelligence collection is conducted with clandestine OPSEC is most adversaries, upon detecting espionage activity, move quickly to render useless anything that was purloined. For example, clandestinely photographing an enemy’s communication code books. If the collection activity is discovered, the enemy will stop using the compromised codes, and the photographed code book has no further value. Being undetected is paramount in clandestine operation.

• Covert operation: An operation of the United States Government that is planned and executed to influence political, economic, or military conditions abroad, where it is intended that the role of the United States Government will not be apparent or acknowledged publicly (i.e.; plausible deniability).

• Clandestine and Covert operation: The operation must be undetected, and the sponsor’s identity is concealed.

By the very nature of clandestine operations, they tend to be low-key. Any sort of violence associated with the operation tends to cause the lack of detection to be tossed right out the window.

Covert operations conducted by the CIA, for example, are less concerned about remaining undetected during the operation, or afterwards. Of greater concern is running the operation so it cannot be traced back to the United States. In this sense, it is a fact-of-life that covert operations tend to have more violence attached, destroying property and/or killing enemy personnel to prevent them from reporting who or what they saw. As noted previously, when diplomacy fails, but, direct military intervention is too heavy handed, a plausibly deniable covert operation often becomes the tool-of-choice for resolving vexing problems. Up until Colby’s DCI tour, and the Church & Pike Committees, the CIA regularly conducted operations using all three OPSEC categories. Covert operations bears the majority of public and Congressional opposition. This led Congress to add language in Title 50 U.S. Code, requiring a documented Presidential Finding for covert operations.

Prior to the law being changed to require a Presidential Finding, an extremely sensitive covert operation was usually briefed to the President for his buy-in. The law was moot, however, on any formal requirement to seek the President’s buy-in, nor was there a requirement to document the Presidential Briefing in writing, nor to obtain an actual signature by the President, approving the covert action. Aside from the President’s buy-in, the law was also silent about informing key members of Congress about an impending covert action.

Once the law took effect, all covert actions had to be documented in a signed Presidential Finding, and it had to contain an explanation of why it was necessary to conduct the operation, including the identifiable foreign policy objectives of the United States, and the covert action’s importance to U.S. National Security. Lastly, the Presidential Finding must be presented to both Congressional intelligence committees.

Steve Miller, (c) Copyright 2016

Without regard to making judgments about a country’s Foreign Policy process, lack of process, or flawed process (at least for now), the basic way a nation-state goes about determining their Foreign Policy choices is pretty much the same. Emphasizing a non-judgmental approach to this, all country’s Foreign Policies touch on, to one degree or another: 1.) Goals & objectives a country is looking to achieve abroad; 2.) The principles or ideals that led a country to those goals; 3.) The means or methods to achieve them. Complicating matters, it has become all too prevalent in the past 20 years for non-state actors to start civil wars, insurgencies, and promulgate acts of terrorism. Disruptive non-state actors create infrastructure havoc; often rendering a government unable to develop and pursue legitimate Foreign Policy goals. A sampling of states-in-crisis unable to promulgate a viable foreign policy agenda include: South Sudan, Somalia, Nigeria, Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Yemen, and Chad, to name a few.

In 1962 a German-American political scientist, Arnold Wolfers, PhD, wrote a seminal work entitled, “Discord and Collaboration Essays on International Politics.” In his book, Wolfers was quoted as saying, “decisions and actions in the international arena can be understood, predicted, and manipulated, only in so far as the factors influencing the decisions can be identified.” This is, indeed, the case with many countries in the 21st Century, simply stated, “Why do/did they do that?”

James N. Rosenau was a well-known political scientist, author and academician as a Professor of International Affairs at the George Washington University until he passed away in 2011 at the age of 86. Rosenau developed a theory and method of explanation in 1966 to the question, “Why are the values and goals behind American Foreign Policy resistant to change?” The “Funnel of Causality” to be discussed below is the basis for Rosenau’s theory.

The Constitution makes it clear the President of the United States has the lead role in Foreign Policy development and implementation. The evolutionary nature of American Foreign Policy, however, has developed over the past two centuries into a very pragmatic institution. Those Americans ascending to the Presidency soon find out the pragmatism of the Foreign Policy machine is far more resilient than they ever imagined. As it has been said over and over again, “the Presidency is a lot harder than it looks.”

All American Presidents ponder before, during and after their term-in-office, about their legacy – “what is the mark I made on history?” Whereas, many Presidents thought the country, in general, and the Presidency, in specific, were broken – in need of a major overhaul – they soon found out the Oval Office itself, had equal or greater control over the actions of a Presidential administration than any one occupant.

The phenomenon of “Oval Office precedence” may explain why Democratic Party leaders found President Carter, once in office, to be much less liberal than they hoped for. Or, why was Ronald Reagan a less conservative leader than Republicans thought they were getting? Bill Clinton has been variously described as either “the most conservative liberal” the pundits had ever seen, or, “the most liberal conservative” they ever came across.

These comments and questions are the essence of what Rosenau intended to explain about American Foreign Policy. As it turned out, Rosenau’s concept also served to better understand the Foreign Policy choices of other nations, too.

Rosenau utilized the concept of a funnel to control the flow of what goes into the large opening, and comes out of the small opening…this is the “Funnel-of-Causality.” All external factors, problems and opportunities are part of the funnel opening, labeled “External Sources.” The important thing to remember about the External Sources is they all have the potential of being recognized at the front-end of the Foreign Policy Process before any strategic shaping occurs. Those personnel within a government institution charged with monitoring the outside world, or sometimes it is someone who is not a part of any government, yet, still monitors external sources, like the media, for example, can make a preliminary analysis to decide if the discovery warrants further attention. Whether someone is a formal, global analyst or not, there are far more reasons a discovered external issue stalls or never makes it any farther than simple recognition that “it” is out there.

The key to any external issue getting to the next level, “Societal Sources,” is if those conducting surveillance of the external landscape come across something either good or bad, that they know has some interest to a portion of society in the country under review. If the external issue, however, does not have enough public interest warranting the expenditure of time and resources to vet it further, it is going to remain shelved in the Societal Sources section until something changes.

If an external issue is deemed important enough by a country’s society (i.e.; the court-of-public-opinion), “Government Sources,” who are formally charged with deep dive research & analysis, are now going to strategically and tactically pick apart the issue with potential Foreign Policy implications. The inputs and efforts by those individuals and institutions in this source category, as might be expected, have the longest throughput time, if done correctly.

When a Government research analyst engages their “deep dive,” they are going to vet every possible aspect of the who, what, why, when, where, how, and an estimate of the cost & resources to do something about the issue at hand. A third and fourth aspect in this category is any past precedent, and vetting for possible legal constraints.

Legal constraints in a country like the United States can present a formidable challenge to forward movement of a Foreign Policy issue. Not only are the U.S. Constitution, and codified law taken into consideration, but, case law (i.e.; Supreme Court decisions), Executive Orders, Presidential Findings (authority to take covert and/or clandestine action by the Intelligence Community), and treaties must figure into a decision to stop or delay forward progress of a Foreign Policy issue.

The Role Sources category is comprised of those positions, or jobs within any government whereby a person’s role can affect the outcome of a Foreign Policy decision. A governmental role may be similarly defined based on a legal, or other pre-existing requirement, and precedence. The constraints of a role-based source include those placed on the President, the National Security Council, the Director of National Intelligence, the Secretary of State, and the DOD Secretary, to name a few. As much as a role player has their own personal feelings about a Foreign Policy issue, they may have certain role-based constraints that tend to shape the official policy position, and there is no room for personal preference.

An example of this occurred during the Vietnam War. As President Nixon’s administration was managing the Vietnamization process, Congress felt it was taking too long to exit the War. It seemed like each time the Vietnamization process took two steps forward, an evolving situation, like North Vietnam’s invasion of the South in March 1972, caused the exit efforts to take one, large step backwards. This “backsliding” scenario, as Congress saw it, was derailing the Vietnamization program. To prevent more issues from stalling the exit strategy, Congress began writing laws to cutoff funds for American combat operations in Southeast Asia. The Nixon White House kept finding the money elsewhere to continue combat support operations for South Vietnam. Eventually, Congress enacted further legislation to completely outlaw in the region, U.S. military expenditure of any sort of ordnance or munitions. In the case of each new law, Nixon vetoed the bill; but, Congress mustered the two-thirds “super-majority” and overturned each veto.

The Nixon/Vietnam example shows that the Foreign Policy choices of Nixon were within the role-based privileges afforded the President of the United States as the military’s Commander-in-Chief. Congress, taking one-step-at-a-time, enacted legislation to remove the President’s role-based options. Regardless how much Nixon (or Gerald Ford, later on) wanted to promulgate U.S. military support for South Vietnam, they were constrained by laws placed on the Presidential role of Commander-in-Chief. What either President wanted to do, personally, in this Foreign Policy situation was rendered immaterial.

The final segment of the Foreign Policy funnel is the influence of individual people on how the final, developed Foreign Policy position is put-into-play. A good example of an individual source of influence on a U.S. Foreign Policy position, was that of using military force during the unfolding debacle of the Balkan states – Kosovo, Bosnia, Serbia, etc. – and the actual choices of intervention and/or support made by President Clinton. Not only did Clinton, as the President, have the authority as Commander-in-Chief to deploy American ground combat troops to the region, he also had bi-partisan support of both houses of Congress. Clinton chose to only engage the military for air combat; no ground troops were sent.

Why did Clinton make the choice that he did? Many experts felt Clinton was uncomfortable about the possibility of the Balkans War becoming like another Vietnam. It was Clinton’s age group who took the brunt of ground combat and death in Vietnam; Clinton, however, avoided it by not serving in the military. Since he never served in the military, he did not want the label of “talking-the-talk,” but not walking-the-walk. Again, this is supposition by political scientists.

It is easy to see why U.S. Foreign Policy positions change so slowly. The funneling process forces decisions to move carefully. American Foreign Policy outputs take the pragmatic approach, as well as, the “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” philosophy.

A five segmented Foreign Policy Process Funnel is typical, and well understood by western democracies. But, what about governments based on traditional monarchies, dictatorships, religion-based governments, or socialism-based (Communist) governments? The “Funnel” is still applicable, but can be significantly different than the five segment funnel process common to democracies.

For example: A Foreign Policy issue has been identified as something requiring action by the head-of-government in a dictatorship. Since the very presence of a dictator indicates there is a less likely regard for the “rule-of-law,” a Foreign Policy choice often does not go much beyond the Dictator’s personal preference. The Foreign Policy net result is: “whatever the Dictator says it is, is what it is!”

In any form of non-democratic government there is always a possibility of the traditional five-segment Foreign Policy Funnel having one or more levels completely removed, truncated, or otherwise corrupted. Making decisions based on inadequate professional due diligence can result.

It is worth mentioning here, a few comments about the Foreign Policy practices exercised by the Nazi government of Germany from 1933 to 1945. Before going any further, note that Nazi Germany’s Foreign Minister from 1938 to 1945, was Joachim von Ribbentrop. Keep in mind that prior to joining the Nazi Party in 1932, Ribbentrop’s Foreign Policy “experience” was solely based on frequent global travel as a businessman, period. He had no academic standing as a trained foreign policy specialist, nor had he ever held any type of position as a government employee, except as a German soldier in World War I.

Ribbentrop first became useful to Adolf Hitler in 1932 as a secret, backdoor, go-between with the top democratically-elected leaders of the German government. This only occurred due to Ribbentrop’s personal friendship with a couple of the politicians. Ribbentrop’s character traits were probably the worst ones to have as he began mixing it up with career politicians and the Nazis. He was the quintessential “yes man,” or, using a more modern label, a “suck-up.” Ribbentrop was also an opportunist, an inveterate intriguer, and an upwardly mobile wannabe. Ribbentrop’s dislike was nearly universal among the top Nazi leaders, such as Josef Goebbels, Herman Goering, etc. He was intensely disliked by Germany’s professionally trained and experienced military leaders.

Ironically, looking at the outcome of World War II, the Allies benefited, to a certain degree, by a cadre of German Nazi leaders like, Hitler, Ribbentrop, Himmler, et al, who lacked the education and professional credentials to be in the offices they held. With Germany being one of the most well educated, technologically & socially advanced countries in the World, if the cream-of-the-crop rose to the top across the entire government instead Hitler & his cronies, the World might have looked vastly different today. To be sure, the likes of Joaquim von Ribbentrop induced the Nazi government to be far more extreme than what might have occurred without someone fanning-the-flames. In an interview after the War, a Ribbentrop aide said: “When Hitler said ‘Grey’, Ribbentrop said ‘Black, black, black’. He always said it three times more, and he was always more radical [than Hitler].” It was not a case of Ribbentrop holding more radical personal beliefs than Hitler and other top Nazis. Ribbentrop’s approach was to take whatever idea Hitler expressed, and turn it into a “BIG idea.”

The results of the Hitler/Ribbentrop-led German Foreign Policy apparatus gave Ribbentrop all of the notoriety & recognition he could ever want: He was tried and convicted at the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal after the War. Many top Nazis committed suicide at the end of the War, including: Hitler, Goebbels, Goering and Himmler. Ribbentrop, however, was convicted in a court-of-law, and was one of the few remaining top Nazis who were actually executed for their crimes.

I have discussed all of this to illustrate what often happens to a country’s Foreign Policy apparatus in the hands of an illegally-formed government. Policies, practices, pragmatism and rule-of-law are thrown out the window. In a toxic political climate like this, a disciplined Foreign Policy apparatus is often dismantled, circumvented, or poisoned. It is no longer based on “the will of the people,” but, a misshaped viewpoint of the few. As much as a careful, pragmatic Foreign Policy process may frustrate some people, the number of correct choices far outweigh the gaffs. This then, illustrates how far off-kilter a country’s Foreign Policies can become without some sort of structure and rigor-of-process.

In summary, by using the Policy Funnel in any country, it smooths-out the rough political, legal, ethical and moral edges via a conservative path that makes decisions with greater insight & care. It is far less likely for a head-of-government to promulgate a poor (read: bad) Foreign Policy choice when Rosenau’s Funnel, or something like it, is the basis of the process.

Steve Miller, Copyright (c) 2016