Tag Archives: army

RNSK Vol 2, Edition 7

What Was it Like as an Army Helicopter Door Gunner in Vietnam?

Published July 20, 2022

In terms of all forms of air combat across all services in the Vietnam War, the most dangerous job was Army air crewman on a Bell UH-1 “Huey” helicopter flying the new, highly successful air assault missions.

The Korean War (1950-53) revealed some important facts about helicopters: 1.) They were essential to ground combat and needed some serious RDT&E money to take advantage of the potential, and; 2.) Airborne assaults using paratroopers were an essential asset, but limited in terms of putting a platoon or company-sized element on-target without scattering soldiers over a wide area. The right kind of helicopter could revolutionize airborne combat assaults. The Huey helicopter was the game-changing assault platform the Army needed. Now a target could be Air Assaulted with precision, and limited only by the number of Hueys available.

The UH-1 was the first Army helicopter to use a jet engine connected to a transmission that powered the main and tail rotors. It was faster, had more range and climbed faster, too. With hydraulic-assisted controls, pilots said it was like flying a luxury car! They carried a 4-man crew and were designed to carry a 9-man infantry squad. In Vietnam, however, the oppressive heat and humidity robbed all helicopters of a lot of lifting capacity, and limited them to 6 soldiers instead of 9.

The Huey was flown primarily in the basic transport (“slick”) configuration and some as modified gunships. Being a door gunner on a slick and a gunship were very different jobs. Each aircraft had a crew chief with a maintenance mechanic MOS. The crew chief was quasi-owner of the bird, and was charged with keeping it flying, as well as flying on her. Door gunners were not from an aviation MOS; just someone willing to fly, live dangerously, and learned to be a good shot firing from a moving platform. They helped the crew chief work on the chopper, too.

A Huey gunship was adapted to carry (most of the time) forward firing 7.62mm miniguns and 7-tube, 2.75″ folding-fin aerial rockets. Crew chiefs and gunners on Huey gunships were primarily aboard as weapons mechanics and spotters. The Huey gunships were already weight-limited and unable to carry anything other than the four crewmen, the weapons and extra ammo. If the bird ever touched down during combat, it was because it was forced to.

The “slick” version was the most plentiful variant where the flying crew chief and door gunner had M60, 7.62mm machine guns for use as directed by the aircraft commander. A good door gunner realized very early on, the best way to stay alive was to not only shoot well, but to meld as quickly as possible with the crew chief on a day-to-day basis. Since pilots were assigned to fly different aircraft all of the time, crew chiefs and door gunners had to learn to mold themselves into a 4-man team every time they flew with different pilots. This meant acting and doing things to keep everyone safe, the chopper flying and the guns shooting without having to be told. If you did these things on a regular basis as a crew chief & door gunner, the word got around, and pilots felt good to have you “watching their six.”

Ciao,

Steve Miller, IAPWE – Certified & Member

Managing Editor

The Report on National Security Kinetics™

Seattle, WA. USA

vietvetsteve@millermgmtsys.com

Steve Miller © 2022 – All Rights Reserved

Who Are Some of America’s Best Generals and Admirals of All Time?

America’s only 5-star officers, from upper left: General-of-the-Army (GA) Omar Bradley; Fleet Admiral (FA) Ernest King; FA Chester Nimitz; GA George Marshall; General-of-the-Army Air Forces Henry Arnold; FA William Leahy; GA Dwight Eisenhower; GA Douglas MacArthur; FA William Halsey

This is not a simple question to answer with a direct, definitive statement. I like using sports metaphors, and this question reminds me of the oft repeated question of who is the best baseball player of all time? Even if you separate the group into the major categories of pitchers and hitters, it’s still not an easy answer because the game, the equipment, the baseball, and the players themselves have changed so much in the past 100 years. The same argument holds true for America’s military leaders who served across four different centuries. My standard answer to this sort of question recognizes the diversity of talent we’ve had for military leaders. I choose to present the case of America’s best generals and admirals based on their performance during wartime. Before jumping to that discussion, however, I need to cover a few preliminary issues.

The U.S. Congress enacted special legislation during the 1976 Bicentennial to honor General George Washington as the highest ranking American military officer of all time. Only Washington and General John J. “Blackjack” Pershing (of WW I fame) carry the rank of “General of the Armies,” and Washington outranks Pershing. Legislation enacted on Pershing’s behalf in 1919, which awarded him General of the Armies title, gave the option of wearing four or five stars; he chose to wear only four. Prior to the Civil War, the highest rank an Army officer could aspire to was a two-star Major General. When Ulysses S. Grant took command of the entire U.S. Army during the Civil War, he was promoted to Lieutenant General with three stars. It was not until 1917 when America entered the First World War, that Congress authorized the creation and use of four stars with “General” as the formal title.

The U.S. Navy flag officer situation was quite different from the Army. Until legislation was enacted in 1862, again due to the Civil War, “Captain” was the Navy’s highest rank. The War generated a need for greater rank stratification at the senior level, so, Congress created two flag officer ranks: a one-star Commodore, and a two-star Rear Admiral. Two years later, Congress enacted additional legislation to promote David Farragut to a three-star Vice Admiral. In 1866, Congress passed a third round of legislation, promoting Farragut to a four-star Admiral, and David D. Porter to Vice Admiral. Admiral Farragut died four years later in 1870, so, Porter was promoted to Admiral, and Stephen C. Rowan was promoted to Vice Admiral. The Farragut, Porter, and Rowan promotions took place through Congressional legislation on a person-by-person, named basis only. In 1890, Vice Admiral Rowan passed away, and Admiral Porter followed him a year later. For more than 20 years following their deaths, Naval officers could aspire no higher than a two-star Rear Admiral. Congress took no action to promote any of them to a higher rank. It was not until 1915 when Congress finally authorized one Admiral and one Vice Admiral for each of the three U.S. Navy Fleets – the Atlantic, the Pacific and the Asiatic. Until WW II came around, the Navy could have no more than three Admirals and three Vice Admirals, by law. Because of the legal limits on 3-star and 4-star Admirals, it was common practice for the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), and the Vice Chief (VCNO) to be dual-hatted as Commander-in-Chief and Vice Commander-in-Chief of the Atlantic Fleet.

WW II marked the first, and only time, in American history to promote certain leaders beyond the legal limit of a four-star General or Admiral during wartime. Although Congress authorized five-stars for Pershing, it did not occur until WW I was over. Other nations, most notably the British and Germans, have bestowed five-star status on their most senior general/flag officers in past wars, and did it again in WW II. Ever mindful of our Founding Father’s contempt for England’s maintenance of a full-time army and navy in peace time, and the additional tax burden it caused, did not like the idea of adding a 5th star; in essence, creating a “General-of-Generals” and an “Admiral-of-Admirals.” In WW II, however, when President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill created the quasi-formal entity, the “Combined Chiefs of Staff,” it became obvious to the Americans after a couple of CCS meetings that many of the British CCS members held 5-star rank and sometimes gave the impression they outranked all of the American 4-star officers. This uncomfortable situation filtered its way back to Roosevelt. The President did not act immediately; but, eventually he had to do something to level the playing field between the two country’s top military leaders.

Roosevelt took the necessary steps to create the wartime rank of a 5-star General and Admiral. The thornier issue was not so much who ought to get a 5th star, but how to sort out when each one was promoted. Using a rigid military chain-of-command, Roosevelt knew that officers of equal rank determined who outranked who by using each man’s promotion date, or in military parlance, their “date-of-rank.” For the most part, British 5-star officers had dates-of-rank that pre-dated the timeframe that Washington even started thinking about it. Whether the British liked it or not, Roosevelt and his new 5-star officers behaved as equals and avoided situations that might escalate to the point a CCS member felt there was no alternative but to “pull rank” based on dates-of-promotion (rank seniority).

Roosevelt settled the issue of rank seniority amongst the new American 5-star leaders by promoting his top military advisor, Admiral William Leahy, first, on December 15, 1944. In date order, Army General George Marshall came next on the 16th of December; then Chief-of-Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest King on the 17th. At this point Roosevelt had finished leveling the playing field for America’s top CCS members.

By design early in the war, Roosevelt and Churchill endorsed the CCS decision to tap one 4-star officer, American or British, who became the singular military leader for the Allies in each theater of operations. After promoting the three previous men, FDR began promoting the theater commanders from the U.S. military. For this next sequence, since all of the men had more than 30 years of active duty, Roosevelt used their time-in-service. General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the Southwest Pacific theater got his 5th star on December 18, 1944. Commander of the Central Pacific, Admiral Chester Nimitz, came next on the 19th. General Dwight Eisenhower got his 5-star promotion the next day, December 20th. It’s interesting to note that Eisenhower made the fastest ascension to 5-stars of any of the men. On March 5, 1941, Eisenhower held the permanent rank of Lieutenant Colonel. The next day he received his “eagles” as a full Colonel. He was promoted six times in three and a half years. The final 5-star promotion was head of the American Army Air Forces, General Henry “Hap” Arnold on December 21, 1944.

The American military has regularly used the scheme of honoring officers with career-long meritorious service by giving them a final promotion on their date of retirement. This is sometimes referred to as a “tombstone promotion.” Since the number of active duty Generals and Admirals (1-star through 4-star) are set by Federal Law, a tombstone promotion did not upset the balance of Generals & Admirals on active duty. Retirement promotions were a way for the USG to make amends to an officer whom the President could not promote while on active duty. It was a further gesture of thanks for their long service, because retirement at a higher paygrade brought the retiree more money in their monthly retirement check. Both Admiral William Halsey and General Omar Bradley got their 5th stars in this manner with promotion dates of December 11, 1945 and September 20, 1950, respectively.

Which of the preceding 5-star officers was the best? No one can really say for sure. You might be able to narrow the field to three or four men; but, then to apply further filtration would likely result in splitting hairs that historians could argue over for the next 100 years. Let’s just say that each man was an above average officer throughout his career, such that he can thank many different military & civilian officials who recognized, starting as 2nd Lieutenants and Ensigns, that each man’s skill & achievements made him worthy of promotion 10 more times in the four decades to follow. They all deserve America’s recognition for rising to the challenge of war at exactly the right place and time.

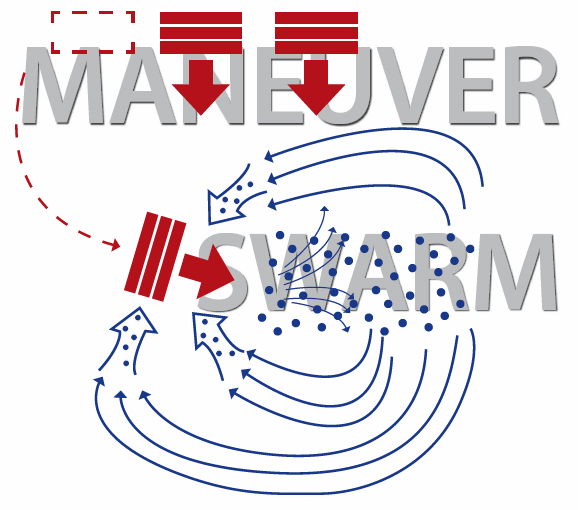

“Swarming” as a Combat Tactic and How to Mount a Defense Against It

Swarming diagram courtesy of warontherocks.com

Swarming diagram courtesy of warontherocks.com

When you look at some of America’s lost military battles, such as Custer’s Last Stand, or the World War II defeat in North Africa at the Kasserine Pass, swarming, or the enemy concentrating their resources against a specific objective, has unfortunately been used effectively against U.S. forces up to modern day. As a ground combat tactic used by the Viet Cong & North Vietnamese Army during the Vietnam War, the enemy overran quite a few Special Forces camps, FOBs, and LRRP (.

Referring to the swarming diagram above, the tactic was used continuously by both the Germans and Soviets during World War II on the Eastern Front. At the high water mark of Germany’s invasion of Russia, the Eastern Front stretched 1,400 miles from the Gulf of Finland in the north, to the southeastern shore of the Black Sea in the south. Throughout the ebb & flow of battle, if either army along that 1,400 mile front pressed forward in one location farther than friendly forces to its right & left, thereby creating a salient (bulge) at the front, it was nearly axiomatic in both armies that any troops left too long in a salient without friendly forces moving-up in parallel, were at extreme risk of swarming from both flanks, thereby losing their route-of-escape out of the trap. Both the Russians and Germans experienced the capture of hundreds of thousands of men due to being surrounded in swarming attacks.

Our understanding of counter-swarming by a small commando or special forces unit is sound advice, and has been successfully used many times. But, what about a larger unit of platoon-size or greater, possessing common infantry skills gained by no more than basic training, plus four weeks of infantry AIT (advanced individual training)? Standard infantry soldiers lack the benefit of more specialized ground combat training received by paratroopers, Rangers, SEALs, etc. This means that if a conventional infantry unit engages in a protracted firefight with a larger enemy force, they lack the more specialized skills, such as DA drills, etc. In this case, the importance is critical for every individual infantryman, and his/her platoon leadership to never stop